Eurocentric Maps: A History of Bias & Exploration

Eurocentric Maps: A History of Bias and Exploration

Eurocentric maps have a long history, from their origins in Renaissance Europe to their peak in 19th-century America.

Since the Renaissance, European exploration, colonialism, and the spread of cartographic knowledge heavily influenced Eurocentric maps. These maps position Europe at the world's core, revealing geographical, cultural, political, and economic preferences.

The Beginning

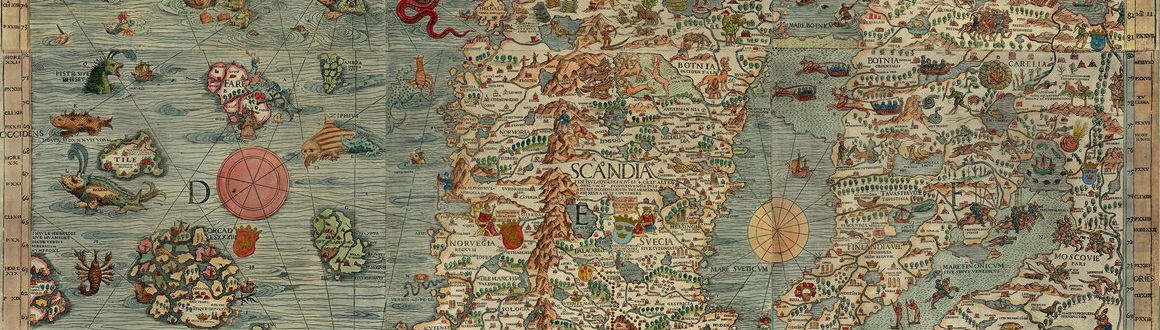

Medieval Europe primarily used "Mappa Mundi" as world maps.

Mappa Mundi are medieval European maps that depict the known world as it was understood in the Middle Ages. They blend geography with history, mythology, and religious beliefs, often centering on Jerusalem and incorporating biblical events, exotic lands, and legendary creatures.

Typically drawn on large sheets of parchment, these maps reflect the medieval worldview rather than precise geographical accuracy, showcasing how people at the time visualized the world’s shape and features.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi, created around 1300, is one of the most famous examples, illustrating a vast array of locations, peoples, and mythical elements. Mappa Mundi are valued not only as cartographic tools but also as cultural artifacts that provide insight into medieval thought and cosmology.

The Mercator Projection's Influence

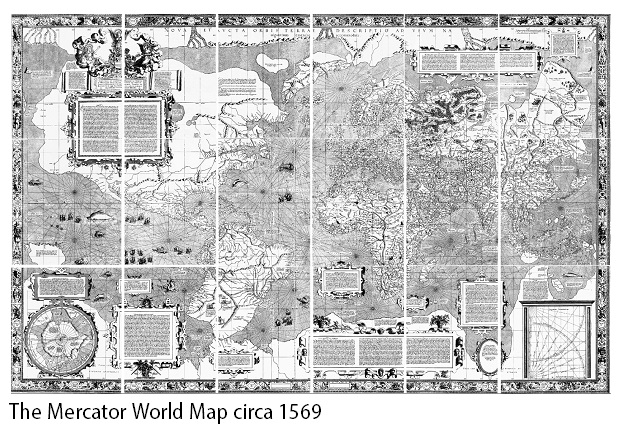

In 1569, Gerardus Mercator introduced the Mercator projection, aimed at navigation.

It quickly became the go-to map in maritime contexts. Despite its popularity, the projection faced criticism for distorting areas, making polar countries seem bigger.

As a result, European nations appeared larger in land area, emphasizing a Eurocentric view that prioritized Europe and its culture, politics, and economy.

Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) was a Flemish geographer, cartographer, and mathematician who revolutionized mapmaking with his development of the Mercator projection in 1569.

This projection enabled sailors to navigate more easily by representing lines of constant compass bearing as straight lines, despite distorting landmasses near the poles.

Mercator's innovation made nautical navigation safer and more reliable during the Age of Exploration. Beyond his famous projection, he produced a comprehensive collection of maps, or atlas, in 1595, posthumously published, that further cemented his legacy.

His detailed approach to cartography and commitment to accurate, usable maps transformed the way the world was viewed and navigated, making him one of history's most influential figures in the field of geography.

The Age of Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism and imperialism spread the Eurocentric worldview by imposing European control and ideology over diverse regions.

European powers partitioned the globe, often drawing arbitrary borders that disregarded local cultural, linguistic, and historical contexts. These boundaries were solidified on maps that served both administrative and propagandist purposes, reinforcing the dominance of colonial powers.

Maps from this period frequently showcased the extent and prominence of European colonies, using symbols and color schemes to highlight colonial territories and trade routes, often at the expense of accurately representing indigenous lands and communities.

Indigenous cultures, traditions, and geographical knowledge were typically marginalized or omitted, reinforcing European dominance and diminishing the visibility and significance of native societies. This cartographic approach not only facilitated colonial administration but also contributed to a global perception that prioritized European interests and perspectives, often erasing or distorting the diverse realities of the colonized regions.

From the 20th Century Onwards

Although various map projections and global perspectives are now available, many maps still predominantly feature Europe at the center. However, this trend is gradually evolving. Awareness of traditional cartography’s biases has spurred efforts to develop more inclusive maps that reflect a global viewpoint.

Eurocentric maps, rooted in the era of European exploration and colonialism, elevate Europe's significance by centralizing it in the world's narrative. While these maps were essential for navigation and governance, they are increasingly criticized for perpetuating colonial prejudices.

As awareness of these issues grows, there is a concerted effort to create more equitable and diverse cartographic representations that honor the complexity and richness of all regions.

Why Mercator Projections are out - and Why Equal Area is in

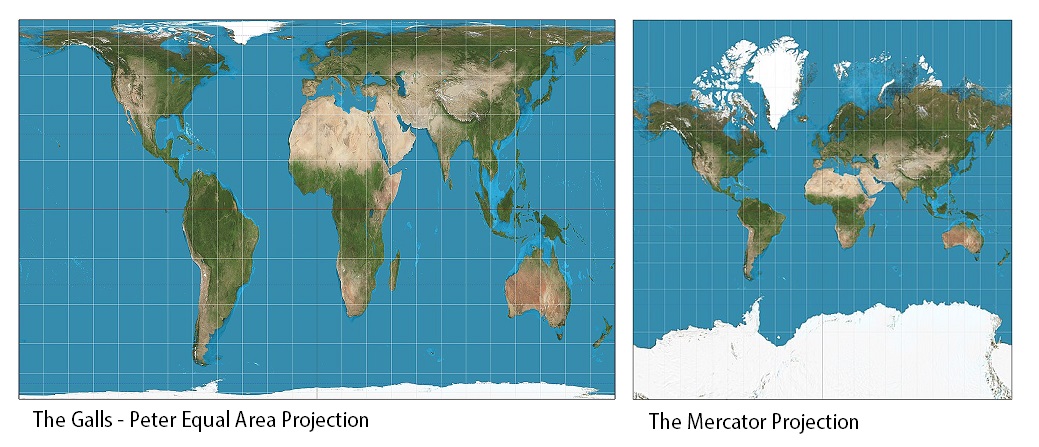

However, these projections significantly distort the sizes of landmasses as they move away from the equator, exaggerating the sizes of regions near the poles (like Greenland) and minimizing the sizes of equatorial regions (like Africa).

They sacrifice some degree of shape and angle accuracy in order to provide a more faithful representation of areas on the Earth's surface.

This shift is driven by a desire for fairness and accuracy in how different regions are depicted on maps, particularly in educational contexts where traditional maps may have inadvertently reinforced perceptions of Western superiority or minimized the scale of continents like Africa and South America.

The Peters projection, first introduced in the 1970s, has been part of this movement towards more equitable cartographic representation, challenging long-standing Eurocentric biases in map making and promoting a more balanced understanding of global geography.

/1004/site-assets/logo.png)

/1004/site-assets/phone.png)

/1004/site-assets/cart.png)

/1004/site-assets/dateseal.jpg)

/1004/site-assets/creditcards.png)